Good intentions alone are not enough to reverse our health inequity

In good faith, the U.S. Preventive Task Force (USPTF) changed the Lung Cancer (Lung CA) screening criteria to reduce the burden of Lung CA. However, the change had an unexpected effect and didn’t increase the screening rate among ethnic minority groups as expected [1]. What were the reasons for this surprising outcome?

Lung cancer (lung CA) is the most common cancer worldwide and the leading cause of cancer-related death in the U.S. It has surpassed breast cancer to become the leading cause of cancer deaths in women [2, 3].

We continue to overrate the impact of genetics on disease outcomes at the expense of environmental factors and do not realize that an individual’s zip code is more critical than their gene code in health outcome

Ahmed-digital doc

Tweet

There is an enormous racial disparity in the mortality and morbidity of lung cancer. Black men are 30% more likely to develop and die from lung CA than white men, even though they have lower overall exposure to cigarette smoke, the primary risk factor for lung CA[4].

The incidence in black women is roughly equal to that of white women even though black women smoke fewer cigarettes [4].

In 2014, the USPTF recommended screening for lung CA with a low-dose chest CT scan in smokers 55 years of age with a thirty pack-years smoking history. Unfortunately, this recommendation was tainted with inequality in lung CA mortality and morbidity[1].

Therefore, the USPTF changed the screening criteria in 2021 to 50 years and 20 pack-years smoking to counter this disparity. Unfortunately, despite this noble intention to increase the number of minorities screened and lower mortality, it turned out to be the opposite effect of worsening disparity with a screening of fewer minority groups[1].

This article discusses practical solutions to prevent such unintended worsening of health disparity.

The Culprit for the 2014 recommendation’s bad outcome: Lung cancer research biased sampling

USPTF primarily bases its recommendations on the most substantial evidence possible, mainly from clinical trials about the intended disease. Unfortunately, only 4% of black men were involved in the clinical trial used to formulate the 2014 guidelines despite their higher disease burden. In this situation, the recommendation was built on a biased assumption that eliminated data from the most vulnerable group (black men) [5].

The 2021 Update Recommendation for Lung CA screening was Great in Principle; Why did it Flop?

A study by Narayan et al. to examine the impact of the updated criteria showed an overall increase in the proportion of respondents eligible for lung CA screening. However, minorities (Black, Hispanic, and Asian/Pacific Islander populations) remained less likely than Whites to be eligible for screenings. For example, 14.7% of lung CA screening qualified individuals were Whites, 9.1% were Blacks, 4.5% were Hispanic, and 5.2% were Asian/Pacific Islander [1].

Simply adjusting screening criteria to capture more minorities without access to care will only leave us running a hamster’s wheel.

Ahmed-digital doc

Tweet

Digital health 360 degrees lens

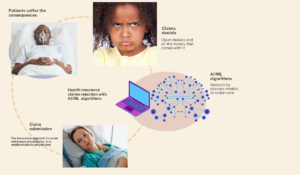

The reason for the Flop with the updated guideline is pretty straightforward. Screening is at the point of seeing a primary care doctor, and minority populations have a disproportionate lack of access to healthcare. More than 29 million uninsured Americans are people of color [6]. Therefore, only modifying screening eligibility will not reduce lung cancer mortality amongst the minority population due to lack of access to healthcare.

No access to primary health care = no possibility of having a CT scan for lung cancer screening. It’s Simple logic, isn’t it?

Secondly, there is an extreme lack of follow-up and eventual treatment amongst the minority group of patients that get screened [7].

Any suspicious lesion discovered in the lungs during screening is just the beginning, as there are multiple follow-up procedures and visits before arriving at the final diagnosis and treatment.

Lack of adequate access to care and other adverse socioeconomic status hinder the minority population from reducing lung CA mortality. Minority groups in the US are less likely to be diagnosed early, less likely to receive surgical treatment, and more likely not to receive any treatment at all [7].

The take-home point here is that simply adjusting screening criteria to capture more minorities without taking a holistic approach to improving social determinants of health and access will only leave us running a hamster’s wheel.

Issues of public health significance are intertwined with the systemic racism baked into our healthcare system.

Technology by itself, no matter how advanced, cannot resolve the issues of our societal inequity and healthcare disparity. In fact, we stand the risk of worsening health disparity with the way we implement health technologies today.

The problem runs deeper than reducing screening criteria and hoping technology (the low-dose CT scan) will eliminate the disparity in lung CA screening.

We cannot fit beautiful, heavy chandeliers in a house on a shaky foundation and expect it to stand. Fancy technology akin to the chandelier without foundational health access will not stand the test of time.